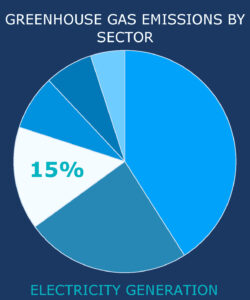

California’s electricity sector is one of the largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions, contributing almost 20 percent of statewide emissions. As a result, the state’s climate change goals necessitate reductions from this sector through energy efficiency measures to reduce demand and by switching to from fossil fuel-based energy to renewable sources.